A West Australian junior involved in a number of exploration projects is confident it has come across an iron oxide-gold-copper (IOCG) deposit in its home state.

Late last year, Miramar Resources Ltd (ASX:M2R) said that a review of historical drilling data had “potentially” revealed very significant magnetite iron opportunities at its wholly-owned Whaleshark project, which sits within the Carnarvon Basin in WA’s Ashburton region.

Field work conducted in the area by Western Mining Corporation (WMC) in the 1990s whilst exploring for an IOCG intersected significant widths of magnetite-rich banded iron formation (BIF) averaging above 25 per cent iron beneath younger sediments ‒ with several holes ending in mineralisation.

Although the junior is realistic enough to know it will probably not find an IOCG-uranium deposit the magnitude of the mighty Olympic Dam in South Australia (which was discovered by WMC during the 1970s and is now owned by BHP), it might be the size of Ernest Henry in Queensland’s Cloncurry region, a warhorse for the now-gone MIM that is currently under the auspice of Evolution Mining Ltd.

According to Miramar, the magnetic anomalies seen at Whaleshark are similar in scale to BCI Minerals Ltd’s Maitland project (which has a resource of 1.106 million tonnes at 30.4 per cent iron) and Iron Mountain Ming Ltd’s Miaree deposit (268Mt at 31.36 per cent iron) – both of which are magnetite deposits in WA.

The target is hosted in a BIF formation and granodiorite under Carnarvon Basin sediments, it has shallow cover (mostly under 100 metres) and contains large surface mobile metal ion anomalies as well as geochemical anomalism within basement unconformity.

From an economic point-of-view the appeal of finding a robust IOCG is not easy to miss.

Aside from its large size (with established projects hosting up to a billion tonnes of ore at 1 per cent copper and 1 gram per tonne gold), it also has the potential to host a number of by-products, including silver, cobalt, uranium and rare earth elements.

With Whaleshark, a larger and virtually untested magnetite target is observed on the southern side of the granodiorite pluton.

Drill testing of the second magnetic anomaly has been limited, with only a handful of historic RC holes that were not assayed for iron, and recent aircore holes completed by Miramar in 2022 that ended in grades of 18 to 32 per cent iron, being completed.

In general, the company said, the basement was significantly shallower within this target, hosting an average cover thickness in the order of 25 to 30 metres.

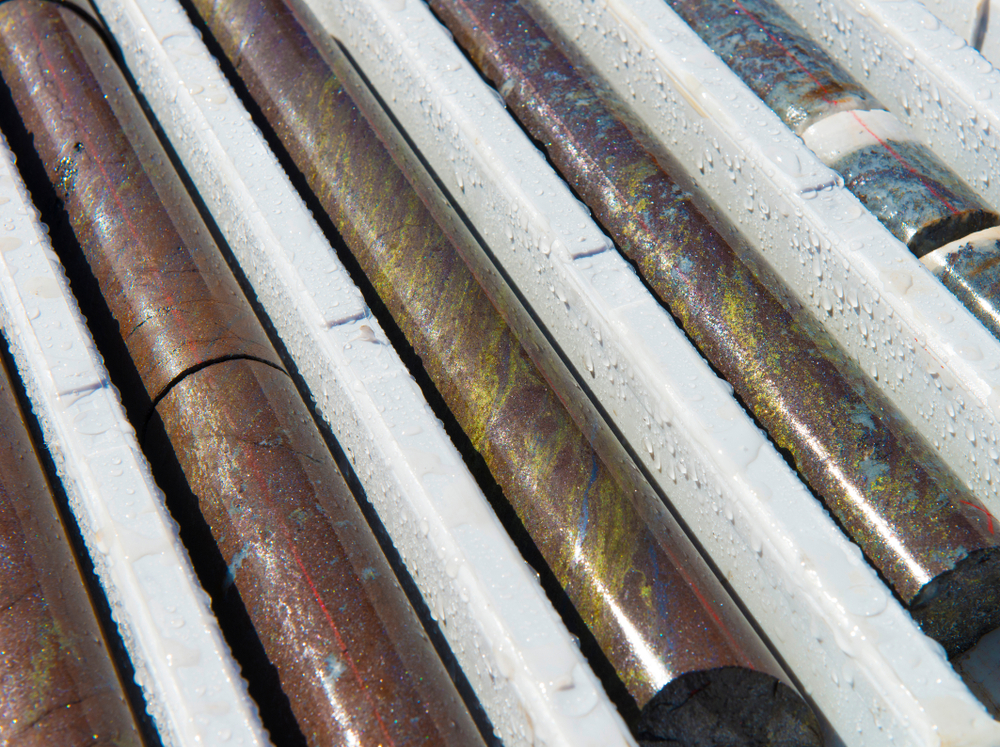

Towards the end of last year, Miramar staff inspected core from the WMC drill holes with consultant Tim Craske, who worked on Whaleshark with Western Mining.

As a result of work completed to date, the junior now believes there is potential for multiple styles of mineralisation within the project area, including, but not limited to, BIF and/or intrusion-related gold, IOCG, magnetite iron as well as roll-front uranium.

It is now expected exploration work at Whaleshark during 2024 will include a low-cost passive seismic survey to map the depth to basement across the site, a heritage survey covering potential drill sites and further aircore drilling to map the basement geology plus or minus the interface geochemical anomalism.

During last year’s December quarter Miramar received assays from its initial diamond drilling program at the site, which was co-funded under the WA Government’s Exploration Incentive Scheme.

Three holes targeting a gravity anomaly within the Whaleshark granite crosscut by a 4km long north west structure were drilled, with one focusing on the southern half of the gravity anomaly and the other two on the structure.

Fine-grained sulphides, including chalcopyrite, were observed throughout two of the three holes. Its presence was confirmed with handheld X-ray fluorescene at the time of logging and returned spot readings up to 1.2 per cent copper from the thin shear observed.