If it acts adeptly, Australia’s manufacturing sector could play an important role in helping the country reach its net zero carbon target by 2050.

According to Beyond Zero Emissions (BZE), bold action by the nation’s manufacturers could result in five onshore ‘clean-tech’ supply chains, which could generate up to $215 billion in revenue and create around 53,000 additional jobs via some “decisive action” to best harness the domestic resources and raw minerals currently on offer.

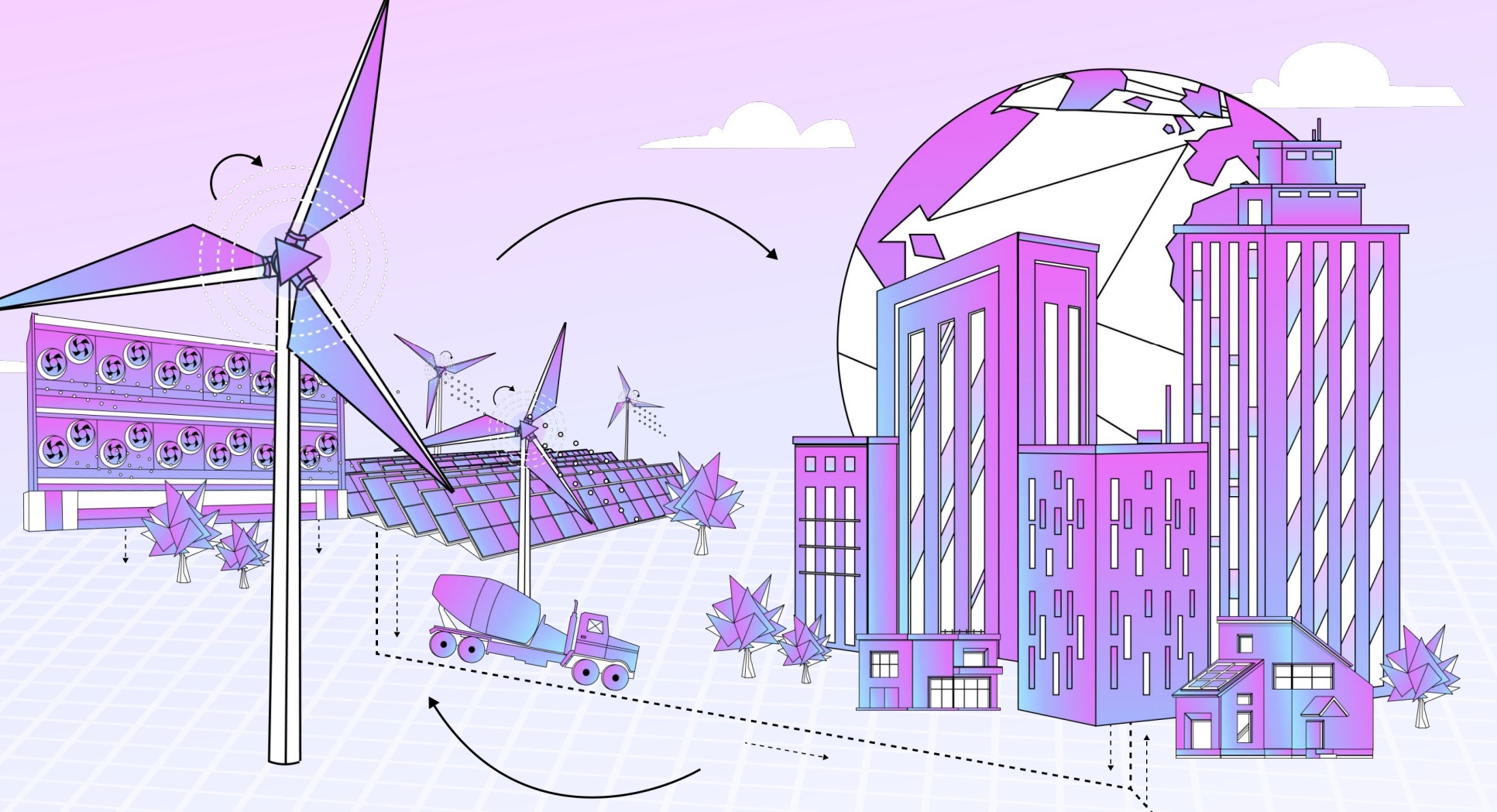

This would involve the production of solar, wind and battery-stored energy sources as well as heat pumps and commercial electric vehicles.

A recent report by BZE suggested that time-limited financial support should be provided to build competitive Australian clean-tech manufacturing industries, thus ensuring the growing demand for domestically generated energy-related technologies.

For all of this to take place, though, there needs to be a focus on manufacturing in clean industry hubs on top of the development of a circular economy.

Battery technologies, BZE said, have emerged as the most promising sector for the country’s economic growth and decarbonisation efforts, potentially creating up to 20,000 jobs and generating $114 billion in revenue by 2035.

Moreover, smart investment in industries and regional communities would encourage places like Gladstone (Queensland), Kwinana (Western Australia) and the Hunter Valley (New South Wales) to diversify from a fossil fuel past and grow a clean technology future.

“From making batteries to recycling steel, the future is already being made in Australia,” BZE chief executive Heidi Lee said.

“We have the skills, capabilities and key technologies needed for a zero emissions economy – let’s put them to work.

“With the right support, Australia can meet global markets’ demand for refined critical minerals and support onshore demand for clean-tech products.

“Smart investment in supply chains is critical for Australia’s energy security, long-term jobs market and decarbonisation efforts.

“We need to build capability at the top and tail of clean-tech supply chains so we are better equipped to capture the benefits from our consumer products right through to waste that we currently have to bury or ship overseas.

“We don’t need to do everything, everywhere and all at once.

“We need to double down on doing more of what we know, and support the communities, industries and businesses already set up and ready to make Australia’s future.”

While this could work, manufacturers are still facing a slew of challenges that may hamper these ambitions, including the growing expectations of the workforce, the challenges facing the implementation of AI, and the fact the country’s economic growth has only been around 1.1 per cent in the past 14 months.

Nevertheless, according to research by the Productivity Commission, Australia’s manufacturing performance has strongly rebounded following the COVID-19 pandemic — with material increases enjoyed in value-adding, employment, exports, financial performance and capital expenditures.

Australian manufacturing, it said, was consolidating into more competitive sub-industries, wherein food, beverages and metals output had grown, but the production of petrochemicals, machinery and other items had declined.

And while there had been tough cost pressures during the recent period of inflation, sales price growth was buoyant.

“Manufacturer margins have improved since the pandemic,” the commission noted.

The Australian manufacturing sector undertook $3.38 million of capex in 2022-23, a 30 per cent increase from 2018-19.

“Manufacturing has outperformed the national average, with all industries (ex-mining) capex growth of 4 per cent during the same period,” the commission said.

“High manufacturing capex reflects new investment driven by strong Australian industrial growth, alongside opportunities created by supply chain disruptions.”

However, labour supply is the most acute pressure on Australian manufacturing today. Job vacancies are at record rates, job turnover is growing and wage growth is at a 16-year high.

The domestic manufacturing industry, the commission said, employed 910,600 people in February 2024 — approximately the same level as a decade ago.

There have been shifts in the composition of the workforce, however, with growth in higher value-add manufacturing sub-sectors.

For example, the workforce in the food, metals and machinery manufacturing sub-industries is around 10 to 15 per cent higher than a decade earlier, while smaller businesses with less than 20 employees have recorded a workforce decline of around 20 per cent.

Recent research conducted by the federal government also notes that artificial intelligence (AI) and computer technology could play a key role in Australia’s energy transition.

The commission said AI had already begun to raise both opportunities and challenges.

Other technological disruptions have shown that disruptive business models could quickly become a normal part of life “but the process of adjustment — in terms of policy, regulation, and structural adjustment – is not straightforward”.

“While technological advancement over time has tangible effects on our lives, it can be difficult to identify their implications for productivity,” the commission said.

First, the scale of its impacts could be significant, with machine-learning models already beginning to automate complex productive processes that were invulnerable to previous waves of automation.

However, its adoption could also present new complexities and risks.

“AI will have implications for trustworthiness, liability (and safe harbour) and raise questions about the treatment of technology as legal entities,” the commission noted.

“The ability for technology to make reliable predictions or solve complex decisions based on vast amounts of data can mean that it is difficult (or impossible) to trace how such decisions were made – presenting a ‘black box’ for users, consumers, or even developers.”

Additionally, the uptake of AI technologies could occur in waves.

“As general use technologies, forms of AI could be applied in numerous ways across different occupations and sectors, and spawn a variety of complementary innovations,” the commission said.

“It could also lead to push-back by those whose businesses or employment is disrupted by AI-based innovations.”

Given the state of digitalisation of the Australian economy, the uptake could occur at scale across multiple sectors at different times, resulting in sequential disruption across the economy.

As a form of (intangible) capital, investments in AI could increase the amount of capital per worker and improve labour productivity by increasing the output.

“AI has the potential to address some of Australia’s most prominent and enduring productivity challenges,” the commission said.

“For instance, Australia experiences skill and labour gaps in a range of occupations — where skills are in global shortage, or where market wages are unable to clear.

“AI has shown potential to augment labour in skilled and knowledge work, opening new opportunities for automation (in part or full) and smarter use of the limited workforce.”